By Monica Ann Walker Vadillo

This blog was originally published in 2016 as part of the Museum’s Comic Creators project. We are reposting it as part of our From the Vaults series to celebrate our exhibition about the history of the series, open until 2 October.

Introduction

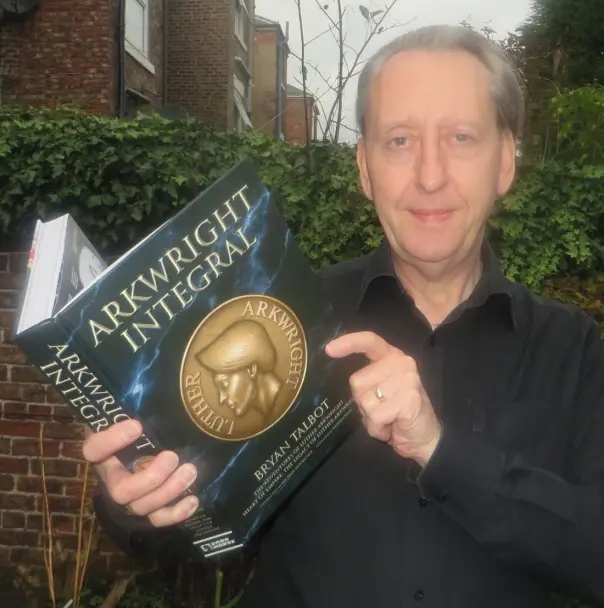

The Comic Creators Project at the Cartoon Museum in London has original artwork from The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, a limited series comic written and drawn by Bryan Talbot between 1978 and 1989. It was followed by a sequel called Heart of Empire: The Legacy of Luther Arkwright in 1995, which was published by Dark Horse Comics. In 2014, this publisher released Arkwright Integral, which combined both stories with an introduction by Michael Moorcock, an afterword by Warren Ellis, and plenty of additional material. This graphic novel is featured in the exhibition The Great British Graphic Novel (20th April – 24th July, 2016).

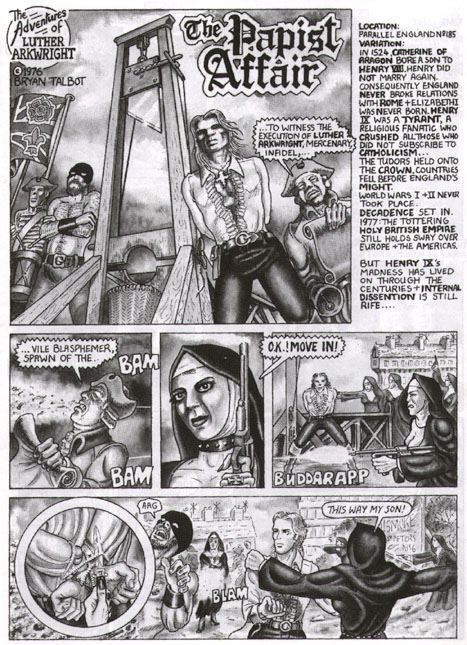

Bryan Talbot, The Papist Affair Brainstorm Comix, 1978.

Luther Arkwright was introduced to the public in a strip published by Brainstorm Comix in 1978. In this strip, titled “The Papist Affair,” the intrepid Luther helps a band of biker nuns to recover the relic of Saint Adolf of Nuremberg, which was being held by “a buncha male chauvinist priests”. Bryan Talbot, in his introduction to the re-printed edition of Brainstorm, mentions that the strip was “an excuse to do a “ground-level” strip in line and water-colour wash and was directly inspired by the Jerry Cornelius stories of Michael Moorcock. After this, Arkwright took on his own personality and I developed his own milieu, but this was his very first appearance.” (Talbot 1999, Introduction).

Luther Arkwright’s adventures continued in 1978 as a serial in Near Myths, a comics magazine published in Edinburgh that only ran for five issues. Afterwards it was picked up by Pssst! Magazine, but its publication was interrupted in 1982 with the story having advanced maybe half way through the plot. Still, it was this same year that the first collected volume of Luther Arkwright was published for the first time by Never Ltd. This book and Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows, published in the same year, are usually considered to be the first British graphic novels, although the serialised form of Arkwright was created four years earlier than When the Wind Blows.

Bryan finished the story between 1987 and 1989 and it was subsequently published as a series of nine standard comic books by Valkyrie Press. A tenth issue titled “ARKeology” was created due to the requests of obsessive fans who rightfully wanted to learn more about the history, production, and background of the characters. This was followed by the three volume trade paperback reprint edition in Britain from Proutt and the American edition of the comic book from Dark Horse Comics in 1990-1991 and 1997. As previously mentioned, Dark Horse Comics would eventually publish the sequel, Heart of Empire, in 1999. The whole story was reprinted in a single volume called Arkwright Integral by Dark Horse Comics in 2014.

The popularity of this graphic novel extends beyond the traditional medium of comics. In 1992 The Adventures of Luther Arkwright was made into a role-playing game (RPG) by 23rd Parallel Games. Interesting enough, and as a sign of how much people loved Bryan’s universe, a brand new Arkwright RPG is currently in production by Hogshead Games. In 2001 there was a three-hour audio drama adaptation of the Adventures of Luther Arkwright by Big Finish Productions starring David Tennant as Arkwright and Paul Darrow as Cromwell. There was also talk about the possibility of taking Luther Arkwright to the big screen in 2006 by Benderspink. It was going to be produced by Andrew Prowse and Sophie Patrick, but according to Talbot, the rights for the project lapsed in June 2010. (Etherington 2010, 34).

Luther Arkwright was digitally remastered by Comics Centrun in 2005 for a Czech edition titled Dobrodružství Luther Arkwrighta. This new artwork was also used in the French edition by Kymera Comics and was the basis for the 2006 webcomic release in the official fan page.

Bryan Talbot and the Valkyrie Press edition of Arkwright were nominated for eight Eagle Awards in 1988, winning four: Favourite Artist, Best New Comic, Favourite Character for Arkwright himself and Best Comic Cover. In 1989 Arkwright won the Mekon Award given by The Society of Strip Illustration for ‘Best British Work’.

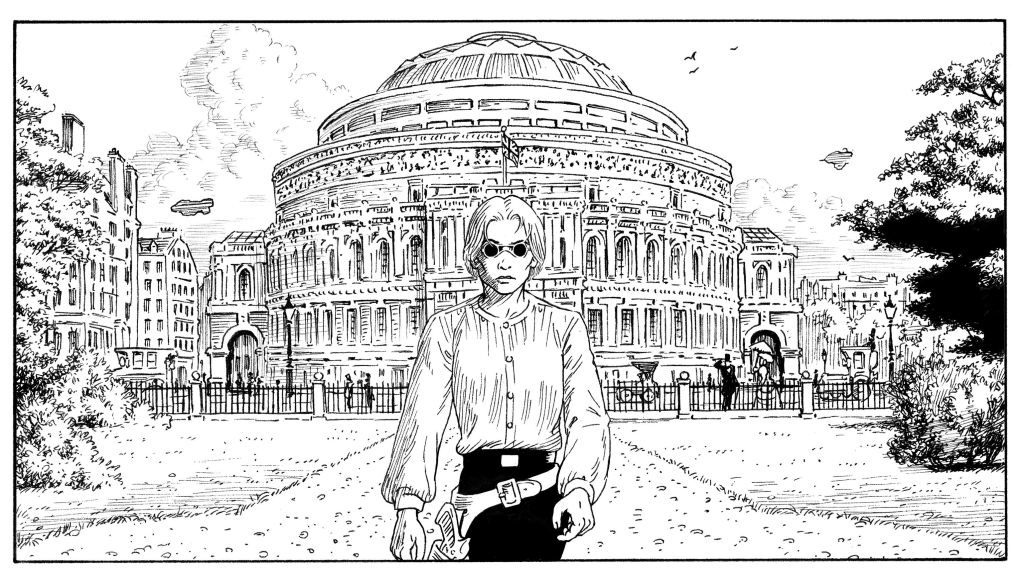

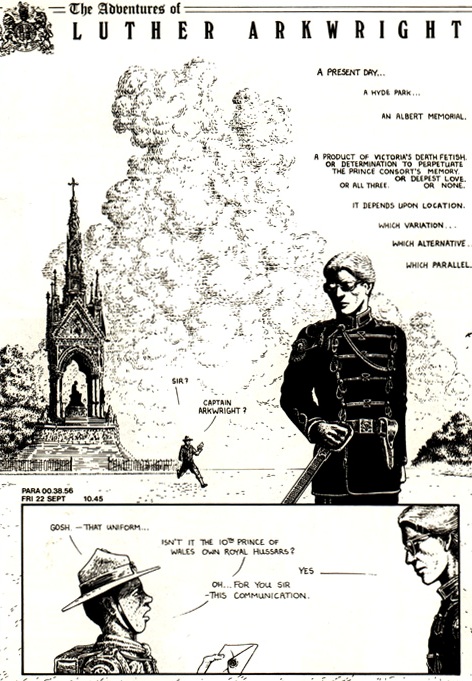

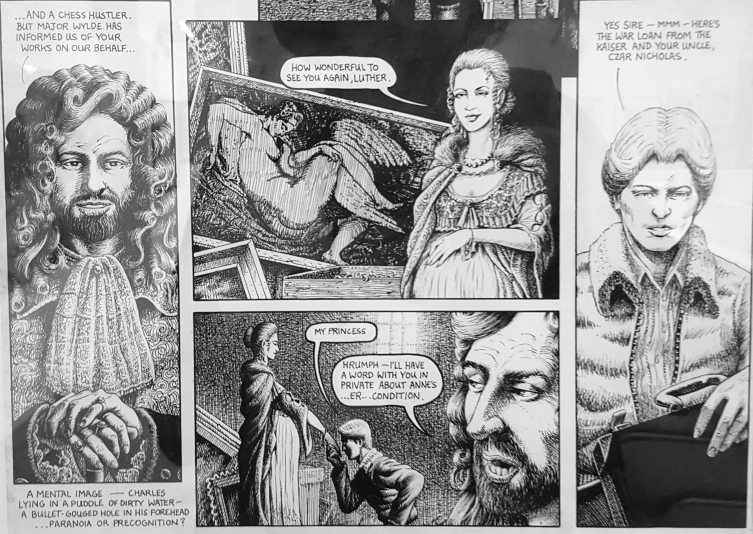

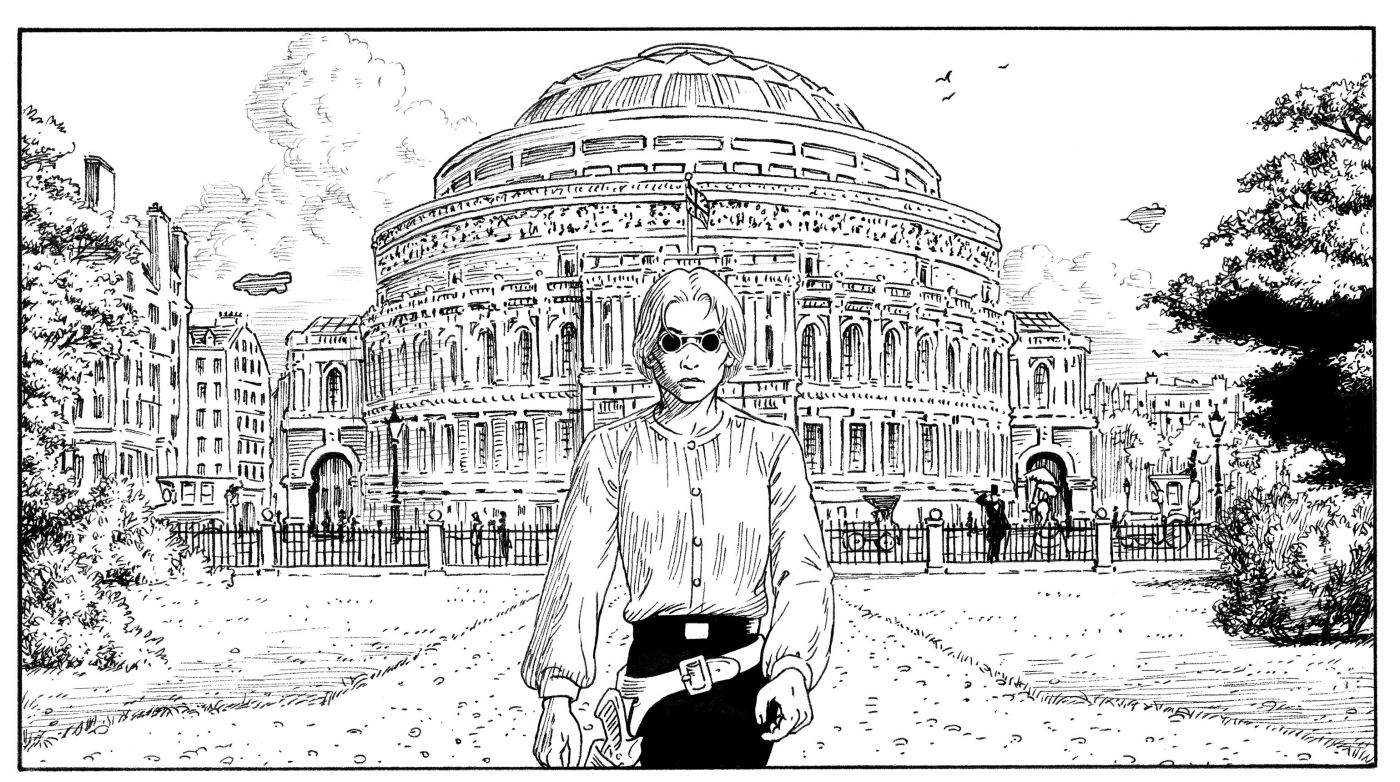

The Adventures of Luther Arkwright can be best described as an epic Steampunk Science-Fiction tale set in a multiverse that the eponymous hero can access by jumping from one parallel world to another. Luther is aided in his missions by Rose Wylde, a telepath that is capable of communicating with the different versions of herself in the multiverse. Both of them work for a parallel called Zero-Zero, whose stable position in the multiverse has made it into a world at peace. It has developed a highly advanced technology that allows it to monitor other parallel worlds for signs of the evil influence of the Disruptors. It is during one of these swipes that Zero-Zero discovers that the Disruptors have gotten ahold of a mystical doomsday device called Firefrost, which is capable of destabilizing and ultimately destroying the multiverse.

Luther and Rose are sent to the parallel world where the Disruptors are hiding the doomsday device. In this parallel, the English Civil War has been indefinitely prolonged due to the actions of these agents. In this world, the monarchy was never restored and Oliver Cromwell’s line continued to rule England with an iron fist-though in this case the puritan religious fervour that characterized it has a distinct darkness to it. Moreover, this political climate has given rise to a royalist uprising that threatens to trigger a second civil war.

Arkwright’s mission then is to destabilize the Cromwellian regime and he intervenes on the Royalist side in order to draw out the Disruptors. At one point, he infiltrates their base, locates Firefrost and destroys it saving the multiverse in the process. Nevertheless, his unit is ambushed, and Luther is killed. Yet his story does not end here. He returns to life in an apotheosic rebirth with his powers enhanced, becoming a new superhuman species in the process.

Mainly done in black and white, the early episodes of the story are rather complex. They present multiple story lines with flashbacks to Luther Arkwright’s upbringing by the Disruptors, his daring escape to his own parallel world, and his early missions for Zero-Zero. All these stories are intertwined with the events taking place during his mission in neo-Cromwellian England. Bryan changes his artistic style and story-telling techniques to match these shifts of place and time. Of particular interest are the scenes of Arkwright’s death and rebirth which are full of religious and mythological symbolism encased in a particularly abstract style. What is fascinating is to see this moment taking place, since from the start the readers and the main character know that he is going to die but details of how this will come to pass are not disclosed.

The last part of the story is more straightforward and linear, showing the evolution of the artist himself in the process (it did take him ten years to complete the story). In the end, Luther Arkwright completes his mission and renounces violence.

On Luther Arkwright by Bryan Talbot

Bryan Talbot has given many interviews along the years which reflect his visionary attitude towards the creation of comics and graphic novels. In The Arkwright Interview conducted by Stephen R. Bissette in 2012, Bryan discusses at length the motivations that led him to create The Adventures of Luther Arkwright. (Bissette 2012)

According to Bryan, The Adventures of Luther Arkwright was a serious attempt to do an intelligent adventure story for adults. As such, he tried to create something as rich as a text novel and drawn in a manner following illustration-quality artwork. In this way he rejected the “short-hand” style that usually characterized the superhero genre. His work was also a reaction against the bland state of mainstream superhero comics of the time. Luther Arkwright contained sex, drugs, his characters swore and vomited, things that would have never happened in a superhero comic of the time…it was the 70s after all.

Regarding the story level, Bryan wanted to move away from formulaic plots usually found in superhero comics. Instead he wanted to create a story that was complex and multi-layered. He wanted for Luther Arkwright to have real depth with subjects like politics, religion, sex, or philosophy being taken into consideration at the same time that he presented an exciting adventure.

According to Bryan “The story itself was directly influenced by French comics. In the late seventies I discovered Metal Hurlant, which blew me away. […] As well as [drawing inspiration from] Moorcock, Luther Arkwright was influenced by the books of Robert Anton Wilson, Alfred Bester, Colin Wilson, and Norman Spinrad. On the visual side, it was very much influenced by the films of Sergio Leone, Alfred Hitchcock, Sam Peckinpah, and, especially, those of Nic Roeg. I tried to translate their techniques of framing, composition and editing-basically, their visual storytelling-into comic form. This led to the comic storytelling techniques in Arkwright that then were experimental but are now pretty much mainstream. I was still learning then (and I still am now) and trying to push the boundaries, so, along with the innovations, there were things that didn’t work. Or drawings that look crap. I made all my mistakes in print. The eighteenth-century British artist and storyteller William Hogarth had a big influence on the illustration style.” (Bissette 2012)

Bryan agrees that from the beginning, Arkwright was self-consciously experimental. He did not use sound effects, thought balloons, wobble lines, and whoosh marks-actually nothing that could be considered cliched, childish or old fashioned by non-comic readers. In the end, he was aiming his work at an adult readership that he hoped would include people who were not used to reading comics. The experimentation included “the twenty-odd-page death/rebirth metamorphosis section, where I employed big blocks of text alongside collaged images, and the assassination sequence where I spread six seconds over seventy-two panels. Today these don’t seem very unusual. When I began The Adventures of Luther Arkwright in 1978, I don’t think that I’d ever seen a slow-motion sequence in an adventure comic before. I put one into the first five pages.”

These are some of the reasons why The Adventures of Luther Arkwright has been acclaimed as a seminal work, i.e. for its combination of historical, science fiction, espionage, and supernatural genres, its experimental narrative techniques and the avoidance of sound effects, speed lines, and thought balloons. Famous comic book creators like Garth Ennis, Grant Morrison, Warren Ellis, Steve Bissette, Michael Zulli, Rick Veitch and Neil Gaiman among others have acknowledged the influence that this graphic novel has had in their work. Currently, Luther Arkwright has a strong cult following and it has inspired many fanzines devoted to the Arkwright mythos as well as short stories written by various authors. The Adventures of Luther Arkwright has been translated and published in eight different countries and his stories continue to sell.

Further Reading

Aldred, Elaine (2012). “Bryan Talbot. A Life of Constant Curiosity and Experiment.” In Strange Alliances: Great Writing Comes in Many Guises. Retrieved on April 17, 2016.

Bissette, Stephen R.(2012) Bryan Talbot-Dreams&Dystopias: S.r. Bissette’s On/In Comics, Vol. 1. Hertford, NC: Crossroad Press. (Ebook)

Etherington, Daniel (2010). “The Making of Grandville” Comic Heroes Magazine 3: 34.

Gordon, Joe (2014). “Director’s Commentary: Filming the Comics Creator.” Forbidden Planet International Blog. Retrieved on April 17, 2016.

Talbot, Bryan (1999). Brainstorm: The Complete Chester P. Hackenbush and Other Underground Classics. London: Alchemy Press.

Talbot, Bryan (2014). Arkwright Integral. Milwaukee, Oregon: Dark Horse Comics.

The Official Bryan Talbot Website. Writer and Artist: Comics, Graphic Novels and Illustrations. Retrieved on April 18, 2016.

Leave a comment